The Supreme Court has refused Aldi leave to appeal against the Court of Appeal’s judgment which held that Aldi’s design on their ‘Taurus Cloudy Cider’ had taken unfair advantage of the repute of Thatchers’ registered trade mark.

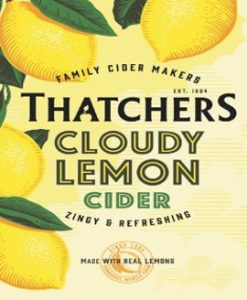

Thatchers applied their registered trade mark (Figure 1) on cans of their ‘Thatchers Cloudy Lemon Cider’. They invested heavily in promoting their product which garnered significant success.

Aldi produced their own “Taurus Cloudy Cider” (Figure 2) using the Thatchers product as a benchmark for quality and design. Conversely, there was no evidence that Aldi had invested in marketing its product.

|

|

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

Thatchers initiated proceedings against Aldi for infringement of their registered trade mark. They were unsuccessful at first instance but appealed, so the case came before the Court of Appeal in respect of s.10(3) Trade Marks Act 1994.

The Court of Appeal decision

The appeal was allowed and it was held that Aldi had taken unfair advantage of Thatchers’ registered trade mark. The Court found that (a) the sign (i.e. the packaging) used by Aldi was similar to the registered trade mark, (b) there was a link between the sign and the registered trade mark in the mind of the average consumer, and (c) that that link caused Aldi to obtain an unfair advantage, as evidenced by the high number of sales, without any marketing spending.

The following points are particularly relevant in clarifying the approach the courts will take to s.10(3) claims under the 1994 Act:

The relevance of a likelihood of confusion

After setting out the legislative framework, the Court examined the key case on unfair advantage, L’Oreal v Bellure, in which it was held that there was no requirement for a likelihood of confusion in order for a finding of unfair advantage. That is to say that where a sign is used in the course of trade which is similar or identical to a registered trade mark, the average consumer may be fully aware of the origin of the goods/services, and still a finding of unfair advantage may be made. This is entirely logical – unlike detriment to the distinctive character or repute of a trade mark, unfair advantage is focussed upon the gains wrongfully obtained by the infringing party. Those gains may arise due to consumers confusing the sign with the registered trade mark, but this need not always be the case. For example, the Court suggested here that Aldi’s intention was to bring the Thatchers product to mind to showcase that Aldi’s product is similar but cheaper – whilst the differing identities of the products remains abundantly clear.

The importance of the advantage being ‘unfair’

After finding that an advantage was obtained, the Court asserted at [117] that the advantage was unfair since it “enabled Aldi to benefit from Thatchers’ development and promotion… rather than competing purely on the basis of the Aldi product”. Surprisingly little more is offered on why the advantage obtained by Aldi is unfair.

The case law of the Court of Justice of the EU, cited by the Court of Appeal, may assist in determining when an advantage is ‘unfair’. For example, in the L’Oreal case, reference is made to the “exploitation on the coat-tails of the mark with a reputation”. When coupled with the Court of Appeal’s findings at [117], it may be inferred that an ‘unfair’ advantage arises where there is no causal link between the advantage obtained and any effort / work / economic activity of the defendant.

On that basis, it seems that the requirement for an ‘unfair’ advantage is largely redundant. To put it another way: where the Court finds that the defendant has taken “advantage” of the registered trade marks’ reputation, there will have to be strong countervailing factors in the defendant’s favour before the court will hold that advantage to be “fair”.

The relevance of the defendant’s intention

The Court sets out at [92] that the defendant’s intention is of evidential relevance to a claim under s.10(3) of the 1994 Act. However, it was clearly noted that the defendant’s intention is not a necessary factor for the claim to succeed. Where the objective effect of the use of a sign is to benefit from the reputation of the registered trade mark, a finding of unfair advantage may be made no matter what the defendant’s intention was.

Practical impacts of the judgment for brand owners and businesses

The Court of Appeal’s judgment underlines the value for brand owners in registering their get up and packaging design as a trade mark.

The judgment also highlights the special protection that the law offers to brands with a reputation, giving security to those brand owners who have invested significant resources into marketing their products and cultivating a reputation. Those brand owners should now have greater confidence that they may succeed against “lookalike” packaging even where there is no likelihood of customer confusion or any express intention by the defendant to take advantage.

On the other hand, businesses such as Aldi offering “like brands but cheaper” might be forced to reevaluate their business models or at least their marketing strategies. For example, Aldi’s use of benchmarking to deliver a product similar to the market leader might require review. It is clear in the Court’s judgment, for instance, that the use by Aldi of the Thatchers design as a benchmark and reference point for its own product and packaging was influential in the ultimate finding that Aldi had infringed.

If you would like to discuss this matter in more detail, please do not hesitate to get in touch with your usual contacts at CSY or via mail@csy-ip.com.

Peter Houlihan and Mikail Ashraf